Is the United States ‘Exceptional’?

Source of the Cartoon: Junior Scholastic

Estudos e Analises de Conjuntura n 18_jul 2021_Is the US Exceptional

By Professor Emeritus Wayne A. Selcher, PhD*

“Every Country is Unique, but the United States is different.” (Everett Ladd)

The Concept of Exceptionalism in National History

Introduction

Debates over issues of national identity have been constants in American history, up to and including today, with the Civil War being the most notable and violent example of serious disagreement about national identity and unity. There are many interpretations of how the country came to be, what its defining characteristics are, and how factual or merely self-congratulatory the elements of the nationalistic claims of exceptionality really were or are now. Like any nationalistic tenet, the exceptionality thesis certainly requires a deliberatively selective and incomplete understanding of the national history. Whole university courses and disciplines of study in American Studies could be devoted to this contentious topic in its broadest sense. The characteristics and conclusions set forth below are not definitive, or exclusive, but are important for foreign students of the United States to take into consideration when trying to understand the formation of the country and the effects of that process today. This essay is meant as a comprehensive introductory overview from an empirical comparative politics and society standpoint. Many links to a wealth of high-quality cost-free online sources in English are offered to assist interested persons who wish to analyze further some aspects of the contemporary situation of the United States in a comparative context.

History of the Concept of “Exceptionalism”

The United States has been the single most influential country in the world since 1945 and has claimed to exercise world leadership since then. The existence of that leadership, its internal contradictions, and its acceptance or rejection by other countries have significant roots in American values, attitudes, and interests, many of which are not widely shared in other countries. The United States was founded by freedom-seeking immigrants deliberately trying to be different from their European homelands– no aristocracy, king, emperor, or state religion. National identity emerged out of a belief system in a country of immigrants, instead of being based on an ethnic origin, as in most of Europe. This national ideology became known as “Americanism” or “The American Creed.” The American Creed, according to Seymour Martin Lipset, in his classic 1996 book American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword, “can be described in five words: liberty, egalitarianism, individualism, populism, and laissez faire.” Lipset noted that such “exceptionalism” has both positive and negative characteristics and consequences, as will be demonstrated below. “Exceptionalism,” as an awareness of U.S. differences from Europe, eventually became one of the components of American nationalism and affects how Americans perceive the world and their role in it. The concept and national motto since 1782 of “E Pluribus Unum” (“Out of many, one”) symbolized the attempt to assimilate diverse ethnicities into a single nation, for many years optimistically referred to as a “Melting Pot” of peoples, now a contested phrase and goal.

Partly because of this diversity of peoples, Americans came to be very protective of the chief national symbols: the flag, the national anthem, and the Pledge of Allegiance. (Yet all three have been the object of controversy and legal cases in recent decades.) The Pledge reads “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” Such a loyalty oath is unusual among the Western democracies and was written in 1892 as a way of uniting the population when it was made up heavily of recent immigrants. In 1954 the phrase “under God” was added, as a testimony to the nation’s religious character at the time and as an anti-Communist aspect. It was recited in the schools as part of the daily opening exercises, and still is in many places. The national anthem is played and sung and the flag is saluted by respect (right hand over heart) on many occasions, including at athletic events and meetings of some civic and political groups. A sharp national controversy about the meaning of the anthem and the flag has erupted in recent years because some athletes, coaches, and managers kneel (“take a knee”) instead of standing respectfully at attention when the anthem is played before a game, in protest of racial injustice. This practice has spread to some other events.

San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick (center) and two teammates take a knee during the US national anthem, in 2016 (Credit: John G Mabanglo/EPA)

American Exceptionalism has frequently been voiced as the assertion that the United States is superior and has a consequent mission of destiny or responsibility, unique among nations, to serve as an example of freedom and liberty for the human race, to pass on to others its success, to lead the world in most areas of endeavor, as a “City on a Hill.” The idea that “the world is watching and judging our success” goes back as far as the writings of some key founders of the Republic, and to some extent before, as in a 1630 sermon by John Winthrop of Massachusetts regarding the Puritan settlement effort that he led. The Declaration of Independence (1776) was framed in idealistic, universalistic, and democratic terms and has served as inspiration for many around the world since then: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Alexis de Toqueville, an astute (an often admiring) French observer, noted from his travels in the new country, in De la démocratie en Amérique. (Democracy in America), Book One, Chapter XVIII, Part VII, 1835, that

“The Anglo-Americans are not only united together by these common opinions, but they are separated from all other nations by a common feeling of pride. For the last fifty years no pains have been spared to convince the inhabitants of the United States that they constitute the only religious, enlightened, and free people. They perceive that, for the present, their own democratic institutions succeed, whilst those of other countries fail; hence they conceive an overweening opinion of their superiority, and they are not very remote from believing themselves to belong to a distinct race of mankind.”

The “exceptionalism” and “mission” concepts eventually became bipartisan, with Republican and Democrat variants, as a symbol of national purpose and defense of freedom and democracy, buoyed especially by the ideals expressed during participation in WW II (“Arsenal of Democracy”) and the Cold War (“Leader of the Free World”). Even though “exceptional,” the United States was often held up as a model for other countries to learn from and emulate. (One could ask, skeptically, if the U.S. is indeed so “exceptional,” so very different, how would other countries be able to emulate it?) At one time or another, most American presidents and many other politicians since John F. Kennedy referred in some form (occasionally vague) to the concept of national specialness as an affirmation of American goodness and, sometimes, concomitant international obligations and commitments. President Ronald Reagan, in his Farewell Address in January 1989, proclaimed famously that

“I’ve spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don’t know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind, it was a tall proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace – a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity, and if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors, and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here.”

For one example of the international consequences of this long-standing value posture, since 1977, because of an oversight mandate from Congress referent to U.S. foreign developmental and military aid programs, the State Department has produced a yearly public report assessing the human rights record of nearly all countries in the world, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.” “The reports cover internationally recognized individual, civil, political, and worker rights, as set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” according to the State Department. Because no other country follows this judgmental practice, it can also easily be understood overseas as a form of American moral tutelage of other nations. In March 2005, in remarks on the release of a new series “Supporting Human Rights and Democracy: The U.S. Record, 2004 – 2005,” Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice implied American moral tutelage of the world in proclaiming that

“In all that lies ahead, our nation will continue to clarify for other nations the moral choice between oppression and freedom, and we will make it clear that ultimately success in our relations depends on the treatment of their own people.”

In what were then practically bipartisan but idealistic sentiments of the U.S. mission in the world, President George W. Bush, in his second inaugural address (January 2005), stated “So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

So ingrained is this long-standing proclivity for judging the internal conduct of other nations, that even during the post-election turmoil of 2020 into 2021, when President Donald Trump absolutely refused for months to accept his November 3, 2020 re-election defeat at the polls, the State Department ironically issued criticisms of the integrity of the electoral process in Venezuela and continued its concern about the political and electoral situations in Nicaragua and Haiti. But the public places a low priority on American efforts to promote democracy abroad.

President Barack Obama and officials in his administration referred to the United States as the “indispensable nation” in world affairs, a phrase earlier used by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in the Bill Clinton administration during the 1990s. In the presidential campaign of 2016, Democrat candidate Hillary Clinton was quoted in The Atlantic as saying to an American Legion military veterans convention that “The United States is an exceptional nation… It’s not just that we have the greatest military, or that our economy is larger than any on Earth, it’s also the strength of our values… Our power comes with a responsibility to lead.”

Secretary of State Madeleine Albright at the White House in 1997 with, from left, Samuel Berger, William Cohen, Bill Richardson and President Bill Clinton. (Credit: Time Life Pictures/White House/The Life Picture Collection, via Getty Images)

In a clear, ironic contrast, departing from traditional (and once almost obligatory) Republican rhetoric, Donald Trump, including in his Inaugural Address, refused to utilize the customary exceptionality designation, but broadcast a more somber “America First” vision of “American carnage” and decay in a nation that would become “great again” only if he were elected president. But the Republican Party platform in 2016 included a section on American Exceptionalism (“the notion that our ideas and principles as a nation give us a unique place of moral leadership in the world”) and referred to the U.S. as the “Indispensable Nation.” A September, 2019 Pew Research Center poll summarized:

“Overall, most Americans say either that the U.S. ‘stands above all other countries’ (24%) or that it is ‘one of the greatest countries, along with some others’ (55%). About one-in-five (21%) say ‘there are other countries that are better than the U.S.’ However, slightly more than a third (36%) of adults ages 18 to 29 say there are other countries that are better than the U.S., the highest share of any age group.”

A January 2021 poll by the American Enterprise Institute noted:

“Despite a lackluster federal response to the COVID-19 outbreak and a violent assault on the US Capitol, Americans remain firm in their belief that American culture and the American way of life are superior to others. More than half (53 percent) of Americans say that the world would be much better off if more countries adopted American values and the American way of life. Approximately four in 10 (42 percent) disagree with this statement.

There is even greater agreement among the public that the US has always been a force for good in the world. Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of Americans agree, while about one in four (24 percent) reject the idea that the US has been consistently virtuous in its actions abroad…

There are massive generational differences in views about American exceptionalism. Young adults are far more likely to challenge notions that the US serves as a moral beacon. Less than half (43 percent) of young adults (age 18 to 29) believe the world would be better off if more countries adopted American values and lifestyle. In contrast, seven in 10 (70 percent) seniors (age 65 or older) agree with this statement. Young adults are also far less inclined to believe the US continues to be a force for good in the world.”

Interpretations of American History and World Role

For most adherents to the exceptionality thesis, the designation of “exceptional” or “special” has been accepted historically as an article of faith, almost self-evident or a priori, as a rhetorical element of July 4 or Pledge of Allegiance-type patriotism (“greatest country in the world!”). In much of the general public, American history is commonly understood as a series of successes, overcoming obstacles, improvement, progress, inventiveness, faith in technology, “can do” optimism, defense of freedom, and a national self-confidence dating back to the “pioneer spirit.”

There is a corresponding longstanding and widespread public belief and dominant narrative that the United States is not aggressive or manipulative in the world, but rather virtuous, defensive, and generous, with the best interests of humanity at heart. According to this view, American goals and wars are therefore not self-interested, but are designed to help others, rid the world of evil, fight oppression and tyranny, and promote global freedom and democracy. (So much so, former President Trump and his adherents would say, that other countries feel free to “take advantage” of the U.S.) But, according to surveys by the Pew Research Center, “People in other nations have long said the U.S. does not take the interests of their country into account when making international policy decisions.”

To many skeptics outside the country, in places where strong American influence is felt, the “exceptional” label is a self-serving superiority complex and has been used mainly to justify U.S. influence, interventions, or hegemony as benign, as a common rationale for empires over the centuries. In any event, it has proven difficult for Americans to understand other peoples with a very different history and culture, such as Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Syria. The reverse is also true.

Regarding the “exceptionality” claim’s acceptance overseas, as published in 2016 in the New York Times:

“Jeremy Shapiro, the research director at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said this idea, though widespread in the United States, is something of a fallacy. Only Americans believe that the United States’ power is inherently virtuous; elsewhere, people see this idea as not only false, but dangerous. “The disjuncture in the way that this is seen abroad and at home is one of the huge problems in U.S. foreign policy,” said Mr. Shapiro, who is American. “This is an image that Americans have of themselves but is simply not shared, even by their allies.”

For historical reasons, Western Europe usually has been at least the implicit frame of reference in the American debate about “exceptionalism.” Public opinion and attitude surveys have shown several key ways in which the United States is indeed significantly different in values and attitudes from Europe, and much of the rest of the world. A 2015 Pew survey found Americans to be more upbeat about the quality of their daily lives than were citizens of other wealthy countries. In a 2016 Pew survey, relative to countries in Western Europe, Americans showed higher levels of individualism, were more likely to believe that they have individual success within their own personal control, tended to prioritize individual liberty over the role of the state, were more willing to tolerate offensive speech, placed more importance on religion in their lives, and were more conservative in beliefs about sexual morality.

U.S. domestic politics plays a key role in the practical consequences of these distinctions. Democrats came to see Western Europe as a model for “progressive” social programs and income leveling, but Republicans emphasized the “exceptionality” idea as a way of justifying their rejection of those “socialistic” European models as inappropriate for the United States. Not surprisingly, the greatest gap in values between the U.S. and Europe in surveys is between Republicans and Europeans. But the main audience for the contention that the United States is “uniquely virtuous” is heavily a domestic one. Few Americans show any interest in or patience for seriously comparing the United States with other countries, such as other Western democracies, in an empirical way on a range of variables for evidence to see if the United States is really “better” or “superior,” either in certain characteristics or overall. (In about the last two decades, some quality Comparative Politics college textbooks have incorporated the United States as a major comparative case study or frame of reference, a departure from previous practice.)

The United States public and its leadership have not shown much interest over time in either foreign views of the United States or explicitly adapting policies or practices from other countries. Nor do the proponents of “exceptionalism” bother to see if that flattering self-designation is widely accepted overseas, or even to concern themselves regularly with the American image around the world, or the image of American leadership abroad, both of which always vary by country. Foreign opinion of the U.S. has also varied in substantial measure according to the particular president at the time, such as the dramatic contrast in opinion registered between Donald Trump and his successor Joseph Biden. Dramatic events, like the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the onset of the war in Iraq in March 2003, COVID-19 response, and the mob attack on the U.S. Congress on January 6, 2021, have also impacted the U.S. image overseas.

Supporters of President Donald Trump breach the U.S. Capitol as election results are to be certified on Jan. 6, 2021. (Credit: Carol Guzy/Zuma Wire)

Major U.S. Differences from Other Industrial Democracies—The American Outlier

Using Empirical Evidence in Comparison

To assess the validity of the exceptionality claim itself, it would be insightful to examine empirically, with evidence, the degree to which the United States is actually exceptional (i.e., significantly different or distinctive) or not among the Western democracies or in some cases worldwide, in some key practices and actual outcomes. Comparative examination of the United States in relation to other countries offers perspectives and insights that allow a more comprehensive view of the country in the light of the practices and achievements or shortfalls of the remaining 95% of the human race. Judgement of which national status as a whole, performance, or practice is “better,” “more desirable,” or even “exceptional” is a normative consideration best made in a holistic assessment and value context, including intangible and philosophical aspects. That task will be left up to the preferences of the reader.

It is important to keep in mind that the sheer size of the United States in the world regarding population (3rd), territory (3rd), and economy (1st) complicates both governance and the degree of accuracy possible in one-on-one comparisons to smaller democracies, such as Denmark or the Netherlands, especially if only size or total output are considered. For example, the economy of California is the size of that of France and the economy of Georgia and North Carolina are both the size of that of Belgium. A per-capita measure is often the most appropriate or accurate way to arrive at a somewhat comparable reading of domestic performance. Comparisons and contrasts by country through international surveys represent only approximations at particular points in time, but they do lend insights from various angles into the changing American way of being. Although we will consider the United States as a whole, regional and social variations and subcultures exist in such a large, diverse, and complex nation, and major changes occur over time on all variables.

1 Different Historical Formation – Less influenced by foreign factors than European countries, regionally dominant with no foreign occupation, and in relative geographical isolation, the United States was able to pursue its own course of development more autonomously than most of the current Western democracies could. The English heritage of grass-roots democracy was coupled with a localistic American distrust or disrespect for authority, especially distant authority. The open frontier and the subjugation of the Native Americans set up settlement patterns favoring individualism and self-reliance, abundant resources, and a tradition of land ownership and respect for private property. (These values are still quite prominent in the culture and conservative voting patterns of most of the open-land American West and Alaska.) Abundant natural resources of a wide variety facilitated national economic development. Under the self-serving justification of “Manifest Destiny,” the United States expanded from Atlantic to Pacific, including annexing Texas and taking a large percentage of the territory of Mexico in a settlement in 1848 after the Mexican-American War, to become the U.S. Southwest and California.

There has been an unusually high degree of stability in the regime (form of government) because the American constitution (1787) was one of the first in written form. It is the oldest written one still in continuous use in the world, if we consider that the constitution of the United Kingdom is not a single written document. The United States was founded on liberalism in the classical sense. This (John) Lockean heritage, however much modified by change, has led in the contemporary period to a relatively limited government, a weak state in contrast to many democracies, and considerable power allocated by the Constitution and practice to the states and localities by the rather complicated system of federalism. Loyalties to the states were strong in the early years of the Republic, and the Founders of the new democracy (a novel form of government at the time) saw dispersal of authority as a protection against tyranny.

A painting depicting the scene at the signing of the U.S. Constitution (Library of Congress/Source: The Atlantic)

A painting depicting the scene at the signing of the U.S. Constitution (Library of Congress/Source: The Atlantic)

The United States adopted a presidential system, also novel at the time, whereas most democracies today use a parliamentary system. Separation of powers and checks and balances among the three branches of the federal government further spread authority, unlike a parliamentary system. The country settled into an essentially two-party system with single-member (winner-takes-all) districts, local bases, low party discipline until recently, and major difficulties in forming third parties, different from many parliamentary systems. After the Supreme Court case of Marbury vs Madison (1803), judicial review of the acts of Congress and the Executive was adopted. This American practice of empowering the top court to declare null and void laws and executive actions that it deems unconstitutional became a model that eventually spread to over 100 countries after WWII.

The Electoral College is unique in the world and an apparently complicated source of puzzlement abroad, since a presidential candidate can win a clear majority of the popular vote in the direct election, but fail to win the office, depending on how the results in each one of the 50 states add up in the Electoral College. This imbalance has happened five times, most recently in the close elections of 2000 and 2016. The Electoral College was a compromise in the Constitution in the 1780s context, to assure smaller states that the larger states in population would not capture the presidency consistently. Even with this curious and controversial institution, however, today the America electoral system overall ranks highly in the world in major authoritative assessments.

2 More Limited Government – An indication of the comparative and relative sizes of governments can be measured by aspects of national government finances (revenue and expenditures). In 2020 only 4 out of the total of 42 countries surveyed by the Organization for Cooperation and Development (Turkey, Ireland, Mexico, and Indonesia) ranked lower than the U.S. (31.52 percent) in General Government Revenue as a percent of GDP. In the same year, only 7 out of 34 countries surveyed by the OECD ranked lower than the U.S. (38.14 percent) in General Government Spending as a percent of GDP. According to the OECD, regarding the latter indicator, “The large variation in this indicator highlights the variety of countries’ approaches to delivering public goods and services and providing social protection, not necessarily differences in resources spent.”

On the two indicators together, only two West European countries ranked below the U.S.—Ireland and Switzerland. In terms of total tax revenue collected at all levels of government, the United States ranked 32 out of 37 at 24.47% of GDP in 2019. The OECD average was 33.84%. The U.S. differs from most OECD countries in the configuration of tax sources as a share of total tax revenue. Unlike 160 countries in the world, and all other OECD members, the U.S. does not use the Value Added Tax (VAT). Most taxes on consumption in the U.S. are at the state and local levels.

3 Strong Individualism – American culture exhibits a comparatively high level of individualism (as in the famous phrase “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” from the Declaration of Independence), and a tendency to prefer individual responsibility over government action. The dominant value system and most public rhetoric are framed in terms of the goal of trying to provide equality of opportunity and “liberty and justice for all” rather than guaranteeing equality of results. In practice, this is an anti-social leveling stance. A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that:

“American opinions continue to differ considerably from those of Western Europeans when it comes to views of individualism and the role of the state. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) Americans believe it is more important for everyone to be free to pursue their life’s goals without interference from the state, while just 35% say it is more important for the state to play an active role in society so as to guarantee that nobody is in need. In contrast, at least six-in-ten in Spain (67%), France (64%) and Germany (62%) and 55% in Britain say the state should ensure that nobody is in need; about four-in-ten or fewer consider being free from state interference a higher priority.”

4 Voting – Voting has never been mandatory (as in some democracies), voter registration is not automatic, and there is no national identification card system. According to a 2021 Pew survey, “Just over a third of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (36%) say it is very or somewhat important for voting to be mandatory for all citizens, compared with a majority of Democrats and Democratic leaners (62%).” Voter turnout in presidential elections is lower than in European democracies and Canada. From Pew, “The 55.7% VAP [voting age population] turnout in 2016 puts the U.S. behind most of its peers in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, most of whose members are highly developed democratic states. Looking at the most recent nationwide election in each OECD nation, the U.S. places 30th out of 35 nations for which data is available.”

Voting rights and election security have become major issues since 2020, with “reforms” often presented in opposing terms. In the U.S., regulation of elections is largely a matter for the states. Following Trump’s vocal lead, Republicans at all levels express concern about election fraud, despite no credible proof that such fraud occurred in November 2020. In 2021, many states under Republican leadership are passing legislation which will tend to make it more difficult to vote, in the name of assuring election integrity. Democrats, in turn, are trying to loosen restrictions to make voting easier. In any case, with 23.5 percent of the members of Congress being female in 2019, the United States is far from being a leader among the nations of the entire world regarding the representation of women in that measure of national politics, even as it promotes the empowerment of women overseas.

Credit: Kenny Holston for The New York Times)

5 Rejection of Socialism – Individualistic values have helped to form a political culture that strongly discourages socialist and Marxist movements and parties, even among the working class, which was one of the strongest anti-Communist groups in the nation during the Cold War. There has been very little interest in extreme ideologies such as Anarchism, Fascism, and Marxism. European-style Socialism never developed a sizable following, even with the emergence of an American-style welfare state under President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Although minority of Americans (especially the young) now have a positive view of socialism and see the downsides of capitalism, on balance, the American political center, broadly defined, is still averse to “socialism” and is to the right of that in Western Europe. And within that more conservative context, a Gallup poll found that in 2020, “Americans’ overall ideological views were about the same in 2020 as in 2019, with 36%, on average, identifying as conservative, 35% as moderate and 25% as liberal.” In 2021, the Republican Party is among the most conservative of major Western parties in its policy positions, with autocratic tendencies under Trump, while the Democrats are close to the Western center.

6 Lower Tax Rates for the Wealthy and Corporations – American political culture and practice have a rather laissez faire attitude toward business and large corporations (compared with many democracies), and favor a large private sector with no state corporations. The U.S. is comparatively corporate-friendly, according to international standards. On the Fraser Institute’s ranking of economic freedom, in 2018, the U.S. placed sixth in the world. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom ranked the U.S. twentieth in the world (“mostly free”) in 2021. Heritage noted in its U.S. profile that “The major obstacles to greater economic freedom in the United States continue to be excessive government spending, unsustainable levels of debt, and intrusive regulation of the health care and financial sectors.”

Composition of tax revenue varies across countries. Individual income tax rates at the U.S. federal level are below average among developed nations, but many U.S. states and localities also levy an income tax and/or a sales tax. The ultra-wealthy can completely avoid paying income tax, or pay only a relatively small amount, because of the way the tax code is framed to their advantage and because of the lobbying influence of rich donors in both political parties. Tax rates on corporate profits in 2019 in the U.S. ranked only two places above the lowest rate among all OECD members. The rapidly increasing gap between CEO pay and that of the typical workers in those American corporations was at a ratio of 320 to 1 in 2019, the greatest disparity among 20 major countries of the world. This combination minimizes income transfers through taxes, comparatively speaking, but allows a higher percentage of disposable income for most taxpayers, relative to more collective societies. For the U.S., in 2008 the OECD found comparatively that:

“Redistribution of income by government plays a relatively minor role in the United States. Only in Korea is the effect smaller. This is partly because the level of spending on social benefits such as unemployment benefits and family benefits is low – equivalent to just 9% of household incomes, while the OECD average is 22%. The effectiveness of taxes and transfers in reducing inequality has fallen still further in the past 10 years.”

7 Regarding its economy, the United States scores very high (Number 2 in 2019) in the Global Competitiveness Report rankings of the World Economic Forum and has one of the highest average incomes per capita in the world, but the income and wealth distributions are unusual. Partly as a consequence of all of the foregoing characteristics, according to the OECD, “The United States is the country with the highest inequality level and poverty rate across the OECD, Mexico and Turkey excepted. Since 2000, income inequality has increased rapidly, continuing a long-term trend that goes back to the 1970s.” Among countries surveyed by the OECD in 2019, members and several non-members, only Costa Rica had a higher poverty rate in the total population than the United States, defined thusly: “The poverty rate is the ratio of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population.”

As is true in most countries, ownership of accumulated wealth (financial assets) is more concentrated in the U.S. than is income. A thorough 2018 OECD study on the distribution of accumulated household wealth by various measures in 28 OECD countries found that:

“Wealth inequality, as measured by the net wealth share held by the top 10% of households, is highest in the United States, followed by the Netherlands and Denmark, and lowest in the Slovak Republic and Japan… Out of the five OECD countries for which several observations are available, wealth inequality increased in both the United States and the United Kingdom since the Great Recession.”

The OECD also found for the U.S., as of 2008, “Wealth is distributed much more unequally than income: the top 1% control some 25-33% of total net worth and the top 10% hold 71%. For comparison, the top 10% have 28% of total income.”

Households with a sufficient income flow in normal times but owning limited wealth assets are far more vulnerable when current income drops in economic downturns such as the Great Recession in 2008 or the COVID-19 restrictions of 2020 and are slower to recover, if they are even able to do so. A 2020 Pew study found for the U.S.:

“The wealth gap among upper-income families and middle-and lower-income families is sharper than the income gap and is growing more rapidly…The wealth gap between upper-income and lower- and middle-income families has grown wider this century. Upper-income families were the only income tier able to build on their wealth from 2001 to 2016, adding 33% at the median. On the other hand, middle-income families saw their median net worth shrink by 20% and lower-income families experienced a loss of 45%. As of 2016, upper-income families had 7.4 times as much wealth as middle-income families and 75 times as much wealth as lower-income families. These ratios are up from 3.4 and 28 in 1983, respectively… the wealth gap between America’s richest and poorer families more than doubled from 1989 to 2016. In 1989, the richest 5% of families had 114 times as much wealth as families in the second quintile, $2.3 million compared with $20,300. By 2016, this ratio had increased to 248, a much sharper rise than the widening gap in income.”

The public is becoming more aware of this unusual degree of income and wealth inequality, although there is little awareness of how unusually high the United States ranks internationally on that measure. A majority of Americans (2020) does say there is too much economic inequality in America, but the sentiment is definitely more pronounced among Democrats and those who lean toward the Democrats (78%) and the general public (61%) than it is among Republicans and those who lean toward Republican identification (41%). Demonizing the rich is not common in the U.S, the economic gap is not a major issue, and a strong public opinion concern about government overreach (the laissez faire component of American culture) works against income redistribution through taxation, even as the wealth and income gaps continue to widen. A GlobeScan survey in 2012 showed that, among 23 countries, only Australia and Canada ranked higher than the U.S. in believing that “Most rich people in my country deserve their wealth,” and the U.S. was one of only 6 countries where a majority expressed that sentiment. In May 2021, according to Gallup, only 2 percent of respondents mentioned the wealth gap as the most important problem facing the country.

For a broader perspective on comparative wellbeing, beyond distribution of income and wealth, the Legatum Prosperity Index is an often-cited project to measure the overall development of countries. To measure “prosperity” around the world, the Legatum Institute uses “12 pillars, comprising 66 different elements, measured by close to 300 discrete country-level indicators, using a wide array of publicly available data sources” to rank countries. In the 2020 Index, the United States ranks 18th in “prosperity” in a list of countries comprising nearly 100 percent of the world’s population.

8 Social Mobility – What about the American promise of social mobility, as the opportunity to work your way up by education, skills, hard work, diligence, self-discipline, thrift, and other personal virtues that the culture prizes? The comparative results are consistently below what most Americans would expect. The World Economic Forum has created a new Global Social Mobility Index, to measure social mobility by country, including the roles of government and business, to demonstrate “why economies benefit from fixing inequality” to maximize human capital for innovation and growth. “Social mobility can be understood as the movement in personal circumstances either ‘upwards’ or ‘downwards’ of an individual in relation to those of their parents.” The 2020 edition ranks the U.S. as number 27 in social mobility in a list of 82 countries/economies. “Among the G7 economies, Germany is the most socially mobile, ranking 11th with 78 points followed by France in 12th position. Canada ranks 14th followed by Japan (15th), the United Kingdom (21st), the United States (27th) and Italy (34th).” A thorough study by the OECD in 2018 estimated how many generations it would take for a person born in a low income family to reach the mean income in their society. The United States fell at 5 generations, below the 4.5 generations average for OECD members.

9 Health Care – Health care has many aspects and contexts, so comparing whole systems objectively and accurately is difficult. In most serious attempts to compare, however, the U.S. does not rank well internationally with other developed countries on either actual public health status or standard health care indicators. Health care is treated as a private, not a public, good. According to a study by the World Policy Analysis Center at UCLA, “The U.S. is the only rich country that fails to provide any nationally-mandated paid sick leave.” Unlike most industrialized democracies, the U.S. does not have a national health care delivery system. The Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) is an insurance arrangement underwritten by the federal government. It is still functional, in spite of many Republican attempts to kill it, but the original requirement for all citizens to have some form of insurance or pay a penalty has been eliminated. The Peter G. Peterson Foundation concluded in 2020 that

“Despite significantly higher healthcare spending, America’s health outcomes are not any better than those in other developed countries. The United States actually performs worse in some common health metrics like life expectancy, infant mortality, and unmanaged diabetes.” The American Public Health Association reported that “Many people find it hard to believe the U.S. performs poorly on most measures of health compared to other high-income countries. But the truth is, study after study supports the same two conclusions: 1. The U.S. spends more on health care but has worse health outcomes than comparable countries around the globe. This holds true across age and income groups. 2. Within the U.S., there are unacceptable disparities in health by race and ethnic group, county by county and state by state.”

10 Race and Ethnic Relations – Unlike the historical experience of most Western democracies, the occupation of what is now the United States by persons largely of European descent was made possible by reducing, dominating, and displacing the Native American population, often through violence, war waged by the Army, and broken treaties. Also, unlike most Western democracies, the U.S. has a history of a large slaveholding establishment on its national territory, mainly in the Southern states, which lasted until the end of the Civil War in 1865, which itself was precipitated to a great degree by the issue of slavery. The legacy of this history, including the disadvantaged position and marginalization of many African-Americans and Native Americans suffering racial inequities in the larger society since that date, has made racial discrimination and inequality a major issue in the national debate. Hate crimes based on race or ethnicity have been on the increase. Racial division was most recently made dramatic by the events leading to the creation of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has gone global, including in Brazil.

Reckoning about these racial issues and injustices toward various groups of persons of color, including claims for reparations, has shaken American politics in recent years, caused urban unrest, and raised issues about policing practices. Standard interpretations of national history in the schools, public monuments, names of schools and athletic teams, and elsewhere are being challenged, with pushback against “Critical Race Theory” and “Cancel Culture” from the conservative elements of society and the media. Whites (those not Latino or Hispanic) made up 60.1 percent of the population in July 2019, Hispanics and Latinos 18.5 percent, Black or African-American (those not Latino or Hispanic) 13.4 percent, and Asian 5.9 percent. Foreign-born persons made up 13.6 percent of the population. The course of this controversial re-examination of racism’s role in the national past and present, in a complicated and increasingly multi-racial society with whites declining as a percentage of the population, deserves careful attention and may lead to a significantly modified national self-image.

11 Religiosity – One of the most distinctive ways in which the U.S. has differentiated itself from Europe (and much of the developed world) is in its higher degree of religiosity. “In God We Trust” is a national motto on the currency, unusual for a Western nation. A 2019 Gallup Poll summary found: “The array of Gallup results leads to the conclusion that putting a percentage on Americans’ belief in God depends on how you define “belief.” If the standard is absolute certainty – no hedging and no doubts – it’s somewhere around two-thirds. If the standard is a propensity to believe rather than not to believe, then the figure is somewhere north of three-quarters.” Americans are consistently clear outliers in the graph of many countries on the importance of religious beliefs relative to average national income. According to Pew: “Nations with higher levels of gross domestic product per capita tend to have lower percentages saying religion is very important in their lives. However, the U.S. is a clear outlier to this pattern – a wealthy nation that is also relatively religious.”

Credit: Stephen Crowley/The New York Times

Numerous international surveys on religion by Pew and other polling organizations in the last decade have shown consistent results. As quoted in Pew’s exact words:

“The U.S. remains a robustly religious country and the most devout of all the rich Western democracies.

Americans pray more often, are more likely to attend weekly religious services and ascribe higher importance to faith in their lives than adults in other wealthy, Western democracies, such as Canada, Australia and most European states, according to a recent Pew Research Center study… As it turns out, the U.S. is the only country out of 102 examined in the study that has higher-than-average levels of both prayer and wealth.

The study analyzed 84 countries with sizable Christian populations. In 35 of those countries, at least two-thirds of all Christians say religion is very important in their lives. All but three of these 35 countries are in sub-Saharan Africa or Latin America. (The three exceptions are the U.S., Malaysia and the Philippines.)

[The U.S.] hasn’t been completely immune from the secularization that has swept across many parts of the Western world. Indeed, previous Pew Research Center studies have shown slight but steady declines in recent years in the overall number of Americans who say they believe in God. This lines up with the finding that American adults under the age of 40 are less likely to pray than their elders, less likely to attend church services and less likely to identify with any religion – all of which may portend future declines in levels of religious commitment.”

In 2018, 72 percent of Americans in a Pew poll said religion is important in their lives, and 51 percent said “very important.” One measure of the relatively conservative nature of American religiosity, and a contrast with more secular or non-practicing Europe, is shown in a Gallup poll of 2019: “Forty percent of U.S. adults ascribe to a strictly creationist view of human origins, believing that God created them in their present form within roughly the past 10,000 years… Majorities of Protestants (56%) and those who attend church at least once a week (68%) believe that God created humans in their present form.” The creationism view and debate have spread from the U.S. to certain religious sectors in Europe, as well as to other areas.

Religious commitment has taken on a strong political significance in the last several decades, in terms of both liberal and (especially) conservative denominations, as each one responds to the changing national society according to its own interpretation of Christianity and secularization. In a 2018 Gallup poll, 41 percent of Americans identified as “born again” or evangelical, a consistent response in recent decades. The large, multi-denominational, conservative evangelical community has been a very crucial strong supporter of Donald Trump and one of his major base constituencies, because of his stance and policies favoring traditional values (“God and Country”), religious freedom, and the anti-abortion movement. A conservative Christian nationalist movement has become a major force in the Republican Party. Religiosity and regular church attendance is lower in the younger generations, so this key aspect of American culture is in transition and will be important to watch.

12 Civilian Ownership of Firearms – The United States is exceptional among Western democracies regarding the widespread civilian ownership of firearms and the presence of a strong “gun culture” with effective lobbying power against further regulations. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimated that the U.S. had 120.5 firearms per 100 residents, as of 2018, far above any other developed democracy. By one 2015 estimate, “31% of all households in the U.S. have firearms, and 22% of American adults personally own one or more firearms.” Firearms ownership has definitely been increasing in recent years, with many first-time owners, partly in response to fears about the COVID-19 pandemic, social unrest, criticism of police conduct, urban demonstrations and riots, and fear of confiscation of firearms by the government. Many owners see the right to own a firearm, including carrying one for self-defense, as an important element of freedom, which is a key national value. The laws vary by state. All states allow concealed carry of a firearm on the person or nearby in public, in most cases only with the proper legal permit from the designated authority. Some states allow concealed carry or unconcealed (open) carry of a firearm in public without a permit.

The United States has a much higher rate of deaths by firearm than any developed democracy, with occasional mass shootings and threats of violence against elected officials. According to the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, regarding rates of homicide by firearm, “Among 64 high-income countries and territories, the United States stands out for its high levels of gun violence… When we look exclusively at high-income countries and territories with populations of 10 million or more, the US ranks first.” The OECD finds, “According to the latest OECD data, the United States’ homicide rate [the number of murders per 100,000 inhabitants] is 5.5, higher than the OECD average of 3.7.”

President Biden began to take on the issue of gun-related crimes, including homicide, in June 2021. Regulation of the possession and carrying of firearms is a highly controversial, emotional issue in both parties, and tends to align with the Republican-Democrat standing on most public issues. One national poll rather typically found in April 2021 that

“Fifty percent of Americans say passing new gun control legislation should be a priority, a drop from 57 percent in 2018, which represented a high-water mark for the issue after the fatal shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Meanwhile, 43 percent of Americans said protecting the right to own guns should be a bigger priority, a jump from 34 percent three years ago.”

As an international impact of this exceptionality, large numbers of guns from the U.S. are continually smuggled into Mexico and Central America, to be used in the drug wars, which are a major driver of the highly controversial mass immigration flow from those areas into the U.S. Thus, the US. is helping to fuel the illegal firearms abroad, the illegal domestic market for drugs, and the illegal mass immigration that plague its society, politics, and foreign policy. CNN reported in 2021 that “About 70% of firearms seized by law enforcement in Mexico and 42% of those seized in Guatemala were first sourced in the US before being trafficked south of the border, according to data from the US Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) as of December 2019. This flow of guns into Central America is known as the “iron river,” and it is vast in scale; according to the Mexican foreign ministry, an estimated 200,000 guns are trafficked from the US into Mexico each year – an average of more than 500 per day.”

13 Incarceration and Capital Punishment – The United States is exceptional among Western democracies in having higher incarceration rates and the use of capital punishment (death penalty). As of 2021, the United States had by far the highest incarceration rate in the world, in terms of the percent of the population in prison. This rate is caused mainly by convictions for drug possession and trafficking and affects Black and Hispanic Americans most heavily. Capital punishment has been outlawed in the European Union, and the EU will not extradite an accused person to a country where capital punishment may result from a conviction. Both the incarceration rate and capital punishment have become civil rights issues, because of the disproportionate number of Black and Hispanic Americans affected by those two practices. As of mid-2021, twenty-three U.S. states have abolished capital punishment, and three have suspended executions, but national public opinion is still in favor of the practice. In 2021, a Pew survey found that 60 percent of Americans favored the death penalty for those convicted of murder, although many of those acknowledged possible unfairness in application and a risk that an innocent person could be put to death. Only 40 percent opposed capital punishment, including 15 percent opposing “strongly.”

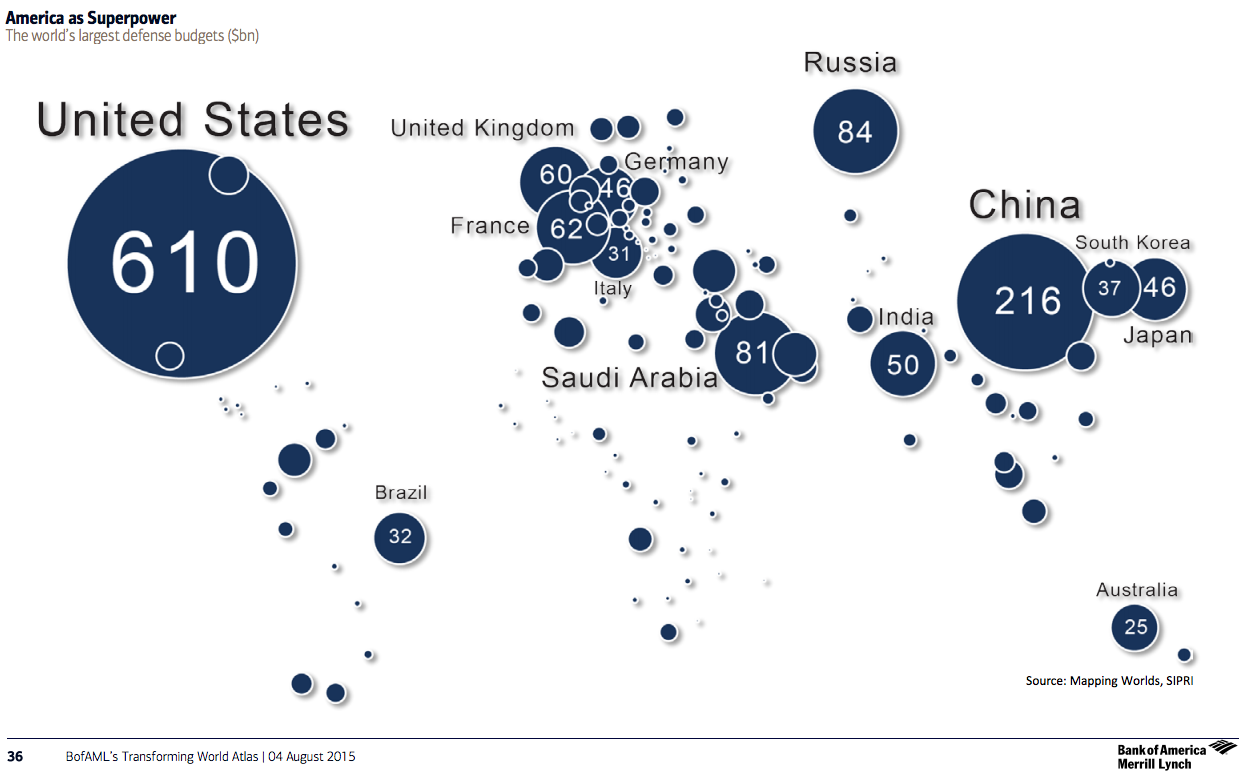

14 Military Spending – Contrasted with other Western democracies, the United States has a much higher relative level of military spending and a large military-industrial complex, as a world power since 1945, with a global presence and strategic influence. Unlike most European democracies, the United States has not fought a military invasion on its own soil since the War of 1812, except for the December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor attack in its then territory of Hawaii. In recent years, the extent of the U.S. military posture, commitments, and involvements around the world has come under question, including from former president Trump, who was seriously considering withdrawing the U.S. from the NATO alliance. The large defense budget, about one-sixth of all federal spending, is generally described as vital by conservatives and criticized by progressives as an obstacle to more desirable social spending, mainly in health, housing, and education. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute notes that “As the world’s largest military spender, the USA accounted for 39 per cent of total military expenditure in 2020.”

SIPRI also noted:

“In 2020 the USA spent almost as much on its military as the next 12 largest spenders combined. The US military burden amounted to 3.7 per cent of GDP in 2020, up by 0.3 percentage points on the previous year… US military expenditure in 2020 was 4.4 per cent higher than in 2019.”

A Pew survey in 2012 found that:

“Americans are somewhat more inclined than Western Europeans to say that it is sometimes necessary to use military force to maintain order in the world. Moreover, Americans more often than their Western European allies believe that obtaining UN approval before their country uses military force would make it too difficult to deal with an international threat. And Americans are less inclined than the Western Europeans, with the exception of the French, to help other nations.”

15 Foreign Aid – Regarding official foreign development and humanitarian aid, the United States has been the largest single national donor in total dollar value for decades. Many American NGOs are also involved in international aid activities of their own accord. Less than one percent of the federal budget goes to foreign aid, and much of what is disbursed goes to the purchase of American goods and services for overseas use, about 67 percent in Fiscal Year 2018. The Brookings Institution stated:

“The relative proportions vary each year, but over time humanitarian assistance accounts for a bit less than one-third of the foreign aid budget, development assistance a bit more than a third, and security assistance about a third. Very little actually is delivered as cash, and most funds for humanitarian and development assistance are provided not to government entities but used for technical assistance and commodities provided by U.S., international, and local organizations.”

When considered as a percentage of the national economy, however, in 2017 the U.S. official foreign aid effort was only 0.18 percent of its GDP, which ranked it lowest on a survey of 27 wealthy countries, a position it has customarily held on that measure for decades, regardless of the party in power in Washington.

Current Challenges to the American Self-image and Role in the World: National Self-Confidence in Decline?

Threats to National Unity and Social Peace

Major value differences between Republicans and Democrats have grown greatly in the last 25 years, and are becoming more “intense and personal.” Ideological differences over cultural issues are now far stronger in the U.S. than in the United Kingdom, France, or Germany. These contentious cultural issues have moral weight and are exactly those that relate to defining American national identity. The heavy moral component in what key actors and some in the public interpret as a struggle over irreconcilable ways of life and incompatible belief systems makes compromise very difficult. With a nearly bipolar configuration between the two parties in their self-definition, terminology, and style, it is becoming hard to generalize accurately about the country’s value consensus as a whole. Several mass media sources have tended to focus on and magnify the disagreements, making the debate more tense and prominent in the public’s mind. For example, compare the coverages and ideological tendencies of Fox News (conservative) and MSNBC News (liberal).

This sharp division about what America has been, is, and should be is usually called the “culture wars.” Some observers are concerned that the basic national consensus itself is severely threatened by the emotional intensity of the struggle between progressivism (“liberalism”) and traditional values and interests (“conservatism”) since at least the early 1990s. Conservatives in particular see secularized popular culture, shifts in definitions of morality, consistent media bias, and ongoing social change generally as presenting an “existential” crisis for their beliefs and way of life They often claim that “woke” liberals have a larger “agenda” to change the country fundamentally and that they “hate America.” Democrats often criticize conservatives as benefiting from “white privilege” in a country dominated by a high concentration of wealth and “systemic racism.” Such deeply-felt intense partisan disparities in moral values on both sides engender anger and hatred for the other side, endanger democracy, and could be a prelude to political violence, with each side self-righteously blaming the other for the outbreak and consequences.

Judging from the public debate, apparently few Americans are aware of the full configuration of the many American “exceptionalities” discussed above. Individual happiness (life satisfaction) is typically high in the U.S., often in contrast to the general public’s more somber assessment of the national situation as a whole. The 2021 World Happiness Report placed the U.S. at 14th in satisfaction with life among the many countries surveyed. On this survey, the social democracies of northern Europe consistently rank highest in self-reported satisfaction with life, year after year.

Overall, there is a growing concern that things are not going well in the country, perhaps in dangerous ways. Social unruliness even extended to an “unprecedented rise in disruptive behavior” on commercial airplanes in early 2021, most often caused by politically-motivated resistance to masking mandates (defending anti-regulation “freedom”). That sense of malaise is part of the reason for the populist support that former president Trump received and still has, in carefully nurturing popular grievances as a “strong, pro-order, no-nonsense, non-politician ‘America First’ outsider” after the “regular, corrupt, globalist” politicians in both parties have so obviously failed. The current national unease and self-doubt have numerous aspects, among others:

- Wavering public trust in leaders, institutions, and each other

- Sense that “the system is rigged” to favor certain privileged interests over the citizens, a point frequently made by Trump

- Concern in some quarters about accessibility of the “American Dream,” although a majority still believes in it

- Political polarization, deeper divisions, extremist ideologies, odd conspiracy theories, and highly contentious, bitter hyper-partisanship

- Declining public sense of U.S. exceptionalism, especially among Democrats and persons under 50

- Concern about the U.S. position in the world

Trends in National Pride, Trust, and Satisfaction

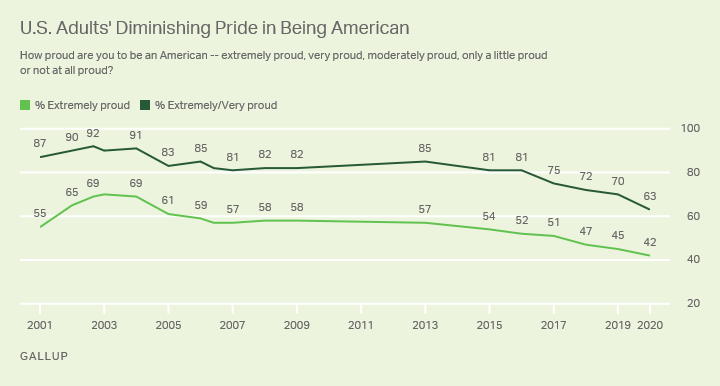

National pride was a traditional characteristic of American public opinion, to a notably higher degree than that found in other Western countries. National pride is now in decline and has fallen to a record low. This phenomenon has also affected Republicans, long the most vocal about their pride in being American. Non-white and younger respondents registered the lowest levels of national pride.

Source: Gallup Poll, June 2020

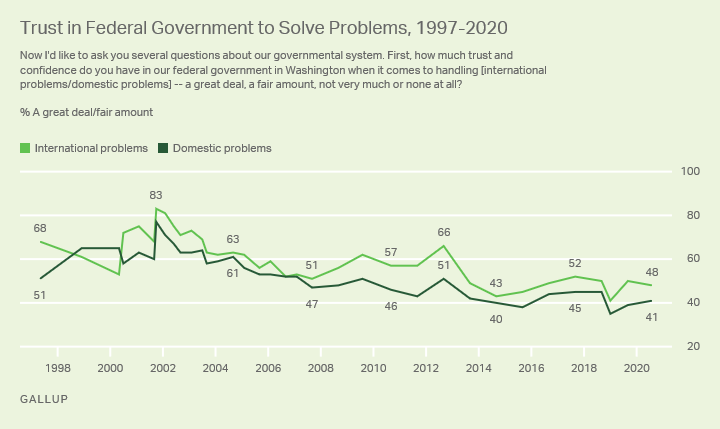

A 2019 Gallup poll indicated that the aspects of the United States that respondents were least proud of were the health and welfare system and the political system. Trust in the federal government’s competence was not high.

Source: Gallup Poll, 2020

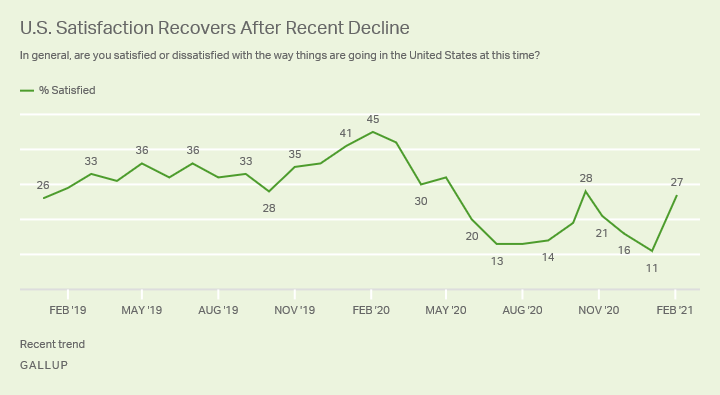

In July, 2020, Americans, especially Republicans, were notably less willing to call themselves “very patriotic” than a year earlier. That same month in 2020, only 13% of Americans were satisfied with the way things were going in the country, thanks largely to the COVID-19 situation. The satisfaction level rebounded in May 2021 to 36 percent, according to Gallup.

Source: Gallup Poll, 2021

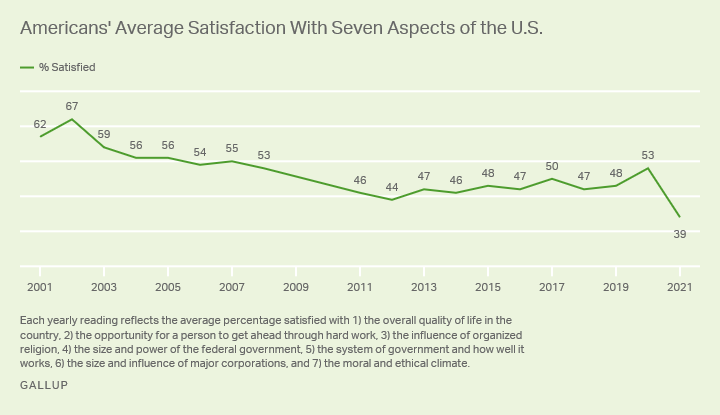

Gallup’s January 2021 “Mood of the Nation” poll showed dissatisfaction with all seven major aspects of American life that comprise that annual poll.

Source: Gallup Poll, February 2021

After the COVID-19 pandemic, American public opinion now seems a bit more open to learning from other countries, perhaps a lessening of one aspect of the “exceptionality” belief. (The adoption of ranked-choice voting, used in several other Western democracies, may be a current example.) According to Pew, in January 2021:

“When asked whether the U.S. government can learn from other countries on dealing with five major issues, a majority of Americans say the U.S. can learn a great deal or fair amount on each… There are major partisan divisions on whether the U.S. could look abroad for solutions to domestic problems. In all cases, Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that the U.S. can learn from other countries, with the biggest differences being on addressing climate change and improving health care… Still, four-in-ten Republicans or more say there can be some benefit to looking at other countries for solutions across each of the policy issues examined.”

Changing Political Culture and National Image Overseas

It remains to be seen if these attitude shifts continue as part of a longer pattern of national self-examination that might lead to a lessoning of the “exceptionality” self-image, or are mainly a temporary result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict and turmoil of the Trump presidency of 2017 to 2021. There is cause for serious concern in 2021, as American political culture and practices are changing in worrisome directions that may not be favorable to democracy. Polls in early 2021 showed an ambivalence in attitudes, with continuing faith in American exceptionality, but serious concern about major US institutions, practices, and shortcomings. A growing feeling that mere partisanship now rules all aspects of government, including the Federal and Supreme Courts, and that “truth” is arbitrary furthers emotional partisan “tribalism” and weakens respect for the guiding objective standard and the rule of law that democracy requires.

Civic knowledge and awareness of history in the population show major weaknesses; only 39 percent of respondents to a poll in 2019 could even name all three branches of government. There is reason for concern that too few citizens and new political actors know and will observe the basic principles of the Constitution and the democratic process. Surveys show a considerable number of Americans would be comfortable with aspects of authoritarian governance, especially the younger generation. The level of tension after the November 2020 election was thoroughly analyzed in a poll by the American Enterprise Institute, which concluded “The January 2021 American Perspectives Survey also revealed that a significant number of Americans appear comfortable with the idea of using violence to address political failures, and across the political aisle, there is widespread agreement that the current democratic system is not working for ordinary people.” Americans customarily thank military veterans for the freedoms they enjoy, but should be aware that most democracies that fail do so because of internal threats, such as violation of democratic norms, high animosity, or failure to deliver, not from foreign invasion.

Changes in the image of the U.S. have been registered at home and abroad. A 2020 survey by Pew Research found that large majorities in Western Europe and the U.S. (65%) believe that their political system needs serious reform. Americans were especially likely to say that their politicians are corrupt, “with two-in-three Americans agreeing that the phrase “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well.” “In the U.S., only 45% of people say they are satisfied with the way democracy is working,” in results of that Pew poll taken before the January 6, 2021 violent storming of the U.S. Capitol by a pro-Trump mob. Pew found that large majorities in France, the UK, and Germany in fall 2020 believed that the “U.S. system needs either major changes or to be completely reformed.” An early 2021 Pew survey of 13 other democracies found that “Few believe American democracy, at least in its current state, serves as a good model for other nations. A median of just 17% say democracy in the U.S. is a good example for others to follow, while 57% say it used to be a good example but has not been in recent years. Another 23% do not believe it has ever been a good example.”

Freedom House noted in the 2021 edition (“Democracy under Siege”) of its widely-referenced annual survey of democracy in the world, that democracy has been declining around the world for 15 years, and “As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny.” Regarding the United States, the report warned:

“The parlous state of US democracy was conspicuous in the early days of 2021 as an insurrectionist mob, egged on by the words of outgoing president Donald Trump and his refusal to admit defeat in the November election, stormed the Capitol building and temporarily disrupted Congress’s final certification of the vote. This capped a year in which the administration attempted to undermine accountability for malfeasance, including by dismissing inspectors general responsible for rooting out financial and other misconduct in government; amplified false allegations of electoral fraud that fed mistrust among much of the US population; and condoned disproportionate violence by police in response to massive protests calling for an end to systemic racial injustice. But the outburst of political violence at the symbolic heart of US democracy, incited by the president himself, threw the country into even greater crisis. Notwithstanding the inauguration of a new president in keeping with the law and the constitution, the United States will need to work vigorously to strengthen its institutional safeguards, restore its civic norms, and uphold the promise of its core principles for all segments of society if it is to protect its venerable democracy and regain global credibility.”

The U.S. is classified as a “flawed democracy” in 2020 by the Economist Intelligence Unit in its latest “Democracy Index” report and is now ranked as the 25th most democratic country in the world, “trailing well behind Canada.” This widely-used comparative index is based on evaluation in five categories: electoral process and pluralism; the functioning of government; political participation; political culture; and civil liberties. In sum:

“The US’s performance across several indicators changed in 2020, both for better and worse. However, the negatives outweighed the positives, and the US retained its “flawed democracy” status. Increased political participation was the main positive: Americans have become much more engaged in politics in recent years, and several factors fuelled the continuation of this trend in 2020, including the politicisation of the coronavirus pandemic, movements to address police violence and racial injustice, and elections that attracted record voter turnout. The negatives include extremely low levels of trust in institutions and political parties, deep dysfunction in the functioning of government, increasing threats to freedom of expression, and a degree of societal polarisation that makes consensus almost impossible to achieve. Social cohesion has collapsed, and consensus has evaporated on fundamental issues—even the date of the country’s founding. The new president, Joe Biden, faces a huge challenge in bringing together a country that is deeply divided over core values.”

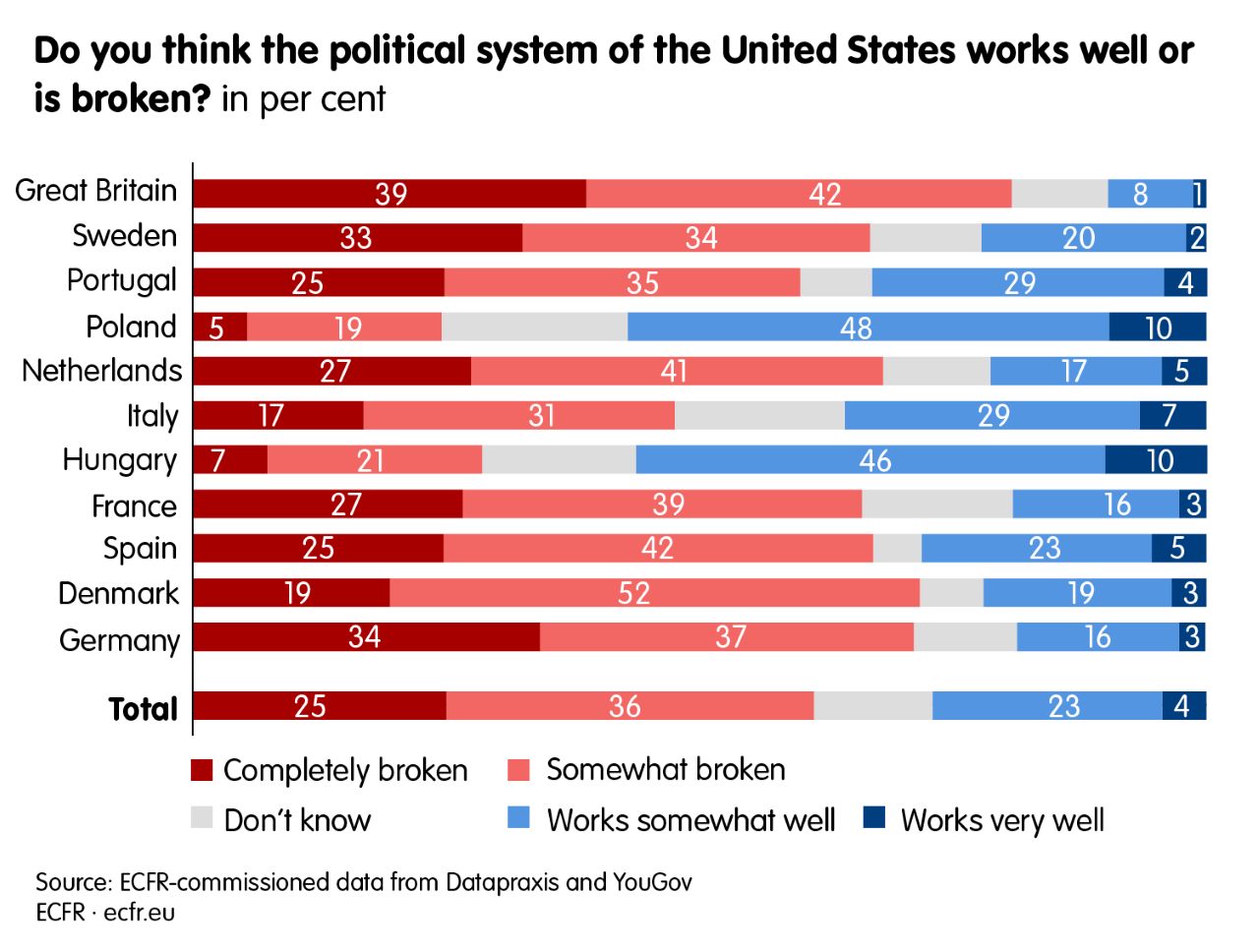

The E.U.’s European Council on Foreign Relations took a survey of European attitudes in eleven countries in early 2021, and concluded from the results that “Americans have a new president but not a new country”:

“Our survey showed that Europeans’ attitudes towards the United States have undergone a massive change. Majorities in key member states now think the US political system is broken, that China will be more powerful than the US within a decade, and that Europeans cannot rely on the US to defend them. They are drawing radical consequences from these lessons. Large numbers think Europeans should invest in their own defence and look to Berlin rather than Washington as their most important partner. They want to be tougher with the US on economic issues. And, rather than aligning with Washington, they want their countries to stay neutral in a conflict between the US and Russia or China… But while Europeans are more positive about the EU, they are very pessimistic about the US. Over six in ten respondents across the 11 surveyed countries believe that the US political system is completely or somewhat broken, and this is also the view of majorities in every country aside from Hungary and Poland.”

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations survey, 2021

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations survey, 2021

A massive 2020 global poll by the Alliance of Democracies found that:

“The world remains split about whether the US’s global influence has a positive or negative influence on democracy around the world: 44% say it has a positive influence, 38% say negative. European countries remain the strongest critics of the US’s global influence, particularly in Germany, Austria, Denmark, Ireland and Belgium where the overall opinion is overwhelmingly negative… Overall opinion of the US’s global influence has also declined in the US itself, dropping 11 percentage points from 33% 2019 to 22% 2020, though still remaining solidly on the positive side of the spectrum.”

Richard Haas, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, the most influential private organization in American foreign policy, noted in Foreign Affairs in an essay titled “Present at the Destruction” after the January 6, 2021 siege on the U.S. Capitol that “Some self-awareness is called for. The United States is not nearly as unique as many Americans believe, including when it comes to the threat of democratic backsliding. What has happened should put an end to the notion of American exceptionalism, of an eternal shining city on a hill.”

To close on a personal note as an American citizen and political scientist, a Brazilian academic colleague familiar with the US told me about US politics in the relatively more stable mid-1990s: “You Americans think you are very different, but you are not. You are deceiving yourselves.” I objected to that view of my country. After the last several years, I have recently admitted to that person that the observation was correct.

Note: I would like to thank my Political Science colleagues Professor Michael Worman, PhD (retired), Professor Kyle Kopko, PhD, Professor Oya Ozkanca, PhD, and Professor Fletcher McClellan, PhD, the latter two of the Department of Politics, Philosophy, and Legal Studies, Elizabethtown College, PA, USA, for their helpful comments on this manuscript.

* Wayne A. Selcher, Ph.D. is Professor of International Studies Emeritus, Department of Politics, Philosophy, and Legal Studies, Elizabethtown College, PA, USA. His major academic interests are Comparative Politics, US Foreign Policy, Latin American Politics and Foreign Policy (especially Brazil), and Internet use in international studies teaching and research. He is the creator and editor of the WWW Virtual Library: International Affairs Resources, a web guide for online international studies research in many topics.

E-mail: wayneselcher@comcast.net.

Estudos e Analises de Conjuntura n 18_jul 2021_Is the US Exceptional